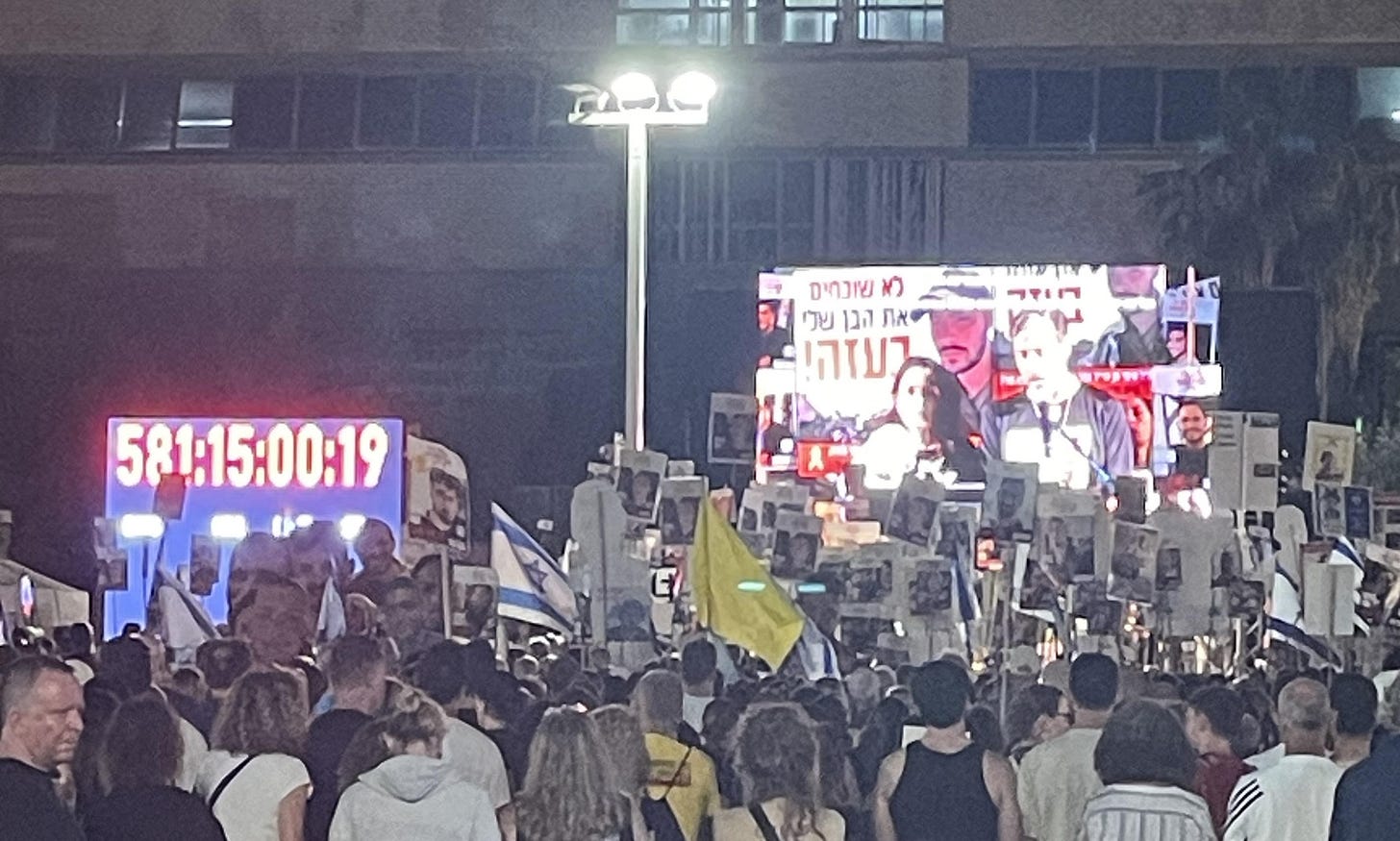

I was in Hostage Square in Tel Aviv last Saturday night, in a crowd of thousands at the weekly protest for the 58 (at the time, 59) Israeli hostages who remain in Palestinian hands in Gaza. It was painful and moving, but also quietly uplifting. Speaker after speaker described their missing family members, pleaded with the world not to forget them, and, more than anything, demanded that their government made returning the hostages the nation’s highest priority.

This call had a sharper edge than usual, because earlier that same week it had emerged in Israeli media that returning the hostages was the bottom of six priorities in the operational orders given to IDF commanders for the looming expansion of the war in Gaza. The previous week, Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu had said that while defeating Hamas was Israel’s “supreme objective”, returning the hostages was only the secondary goal.

Most Israelis disagree: over 60% say that bringing home the hostages should be the priority, even if it means ending the war. Only a quarter say the opposite. It isn’t my place to say who is correct: that right belongs to those whose loved ones are either hostages or IDF soldiers, because they have a stake in it that I do not. Rather, it is to ask a deeper question that falls closer to home: what does supporting Israel mean for diaspora Jews, when there is such a profound and widening division between Israel’s government and its people on the continuation of the war?

It was clear, not just from that evening but from several conversations during my visit (sorry if I didn’t get in touch - it was a short trip), that vast swathes of the Israeli public no longer trust their government. Even the release of Edan Alexander, in which the Israeli government seemed to play little or no part, only served to highlight this schism. It runs deep and touches the most fundamental and sacred aspects of Israeli life: one of the speakers in Hostage Square was the wife of an IDF reservist whose husband has already done 300 days reserve duty since October 7, and has just been called up for another 80 days. If the goal is to return the hostages, she said, then she and her family are unquestionably willing to play their part. But if that is no longer the primary purpose of the war, and when the renewed operation in Gaza is accompanied by rhetoric from the far right of the government about long term re-occupation and the removal en masse of the Palestinian population, why, she asked, should they continue to make that sacrifice?

And yet, at the end of the rally, once successive speakers had condemned their own government and the crowd had booed its ministers, Israeli flags were waved aloft and everyone sang the Israeli national anthem. Despite all the division and heated argument - in which Israel has always excelled - there remains a common understanding that Israel is in an existential struggle it must not lose. Israelis in the south and the north have already experienced what it means to have a fanatical jihadist army just over the border from their homes. Israelis in the central belt, where most of the population lives, now look up at the West Bank hills that loom high on the horizon and wonder whether their turn will come.

This is why debates in Israel over the conduct of the war and criticisms of its government don’t translate in a simple way to diaspora Jewish communities. Israelis - who, let us not forget, face much more immediate and lethal dangers than we do in Britain - can curse and condemn Netanyahu in terms that wouldn’t be out of place in a Guardian editorial, and then sing Hatikvah, wave their Israeli flag, and continue their arguments over dinner in one of Tel Aviv’s fabulous restaurants. But if you are a British Jew who cares deeply about Israel and wants it to win its wars, understands the threats it faces and empathises with its impossible dilemmas; but at the same time, distrusts Netanyahu, despises the far right Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, despairs over this seemingly endless war and worries about the direction this government is taking the Jewish State: there is no landing place for you in British politics and society. No safe space outside the Jewish community to express this combination of views.

There are some, of course, who will not hear a bad word about Israel, no matter what it does or where the criticism comes from (the idea that Israel can do no wrong strikes me as an ironically un-Zionist position, given Ben Gurion’s oft-quoted and possibly apocryphal joke that “When Israel has prostitutes and thieves, we'll be a state just like any other”). But there is no doubt that most British Jews hold a more nuanced set of views, and there is growing disquiet regarding the ongoing war. The recent public letter from 36 members of the Board of Deputies was a crack in the mainstream, not the usual sniping from the fringes, and many British Jews express similar sentiments between themselves. I expect more of these private worries will become public in time: some already have.

I don’t go along with the idea that diaspora Jews shouldn’t give any opinion about Israel other than support. We live in a world where everyone expresses their opinion about everything, online, every day, and it is unrealistic to expect people to keep shtum about the things they care most about. The reason those 36 Deputies wrote that letter is the same reason that other Jews went on social media to condemn them for it: we all care too much about Israel to keep it bottled up.

Finding a ready audience in Britain for criticisms of the Israeli government is not the problem. That much is easy. It is far harder to find people who will hear those criticisms through the prism of the other part of the equation: a genuine concern about the dangers that Israel faces, an understanding that her enemies are, in large part, our enemies, and a serious reckoning with antisemitism here in Britain. We live in a country where Hamas, a fanatical, jihadist terror group with anti-Jewish hate literally written into its founding Charter and more Jewish blood on its hands than any other organisation on earth, has a team of lawyers from respectable chambers working to get it de-listed as a terrorist group. Academics at LSE urge us to better “understand” Hamas while dozens of famous musicians defend the right of Irish rappers Kneecap to proclaim “up Hamas, up Hizbollah” at their gigs (those same musicians, hypocrites and poseurs all, are silent when Jonny Greenwood and Dudu Tassa’s musical collaboration is subject to boycotts and cancellations simply because Tassa is Israeli). Protestors who use the same slogan as Hamas - “From the River to the Sea, Palestine Will Be Free” - to describe their aims, are depicted as peace campaigners and human rights advocates. Few seem to know or care that Hamas’s leaders have repeatedly boasted of October 7 as some kind of heroic victory and vowed to repeat it, while also welcoming the deaths of their own people as a gruesome sacrifice to their murderous “resistance”.

The BBC’s repeated determination to mistranslate Palestinian references to “Yahud” as “Israeli” rather than “Jew” is symbolic of a much deeper desire, that goes well beyond our national broadcaster, to sanitise or ignore antisemitism in the wider pro-Palestinian movement. Few seem to have given any thought at all to why antisemitic hatreds always accompany anti-Israel activism, as if it is just a minor inconvenience not worth considering. The campaign to eradicate the world’s only Jewish state gets treated as a legitimate, respectable view, rather than the racist, hateful politics that it truly is. Zionism - the movement of Jewish national redemption that saved the Jewish people after the Shoah - is demonised, not as a response to Nazism and antisemitism, but as a repeat of it.

In this environment, it is understandable that many Jews do not want to give any satisfaction to Israel’s enemies. Gary Lineker, doubling down on his increasingly extreme, and occasionally antisemitic, anti-Zionism, recently said “The real heroes are the Jews who have spoken out against it”; a statement which only goes to highlight Lineker’s insufferable arrogance, as if he has any idea who Jewish heroes really are. Lineker likes to present his politics as nothing more than compassion, but humanity has to be for all or it is nothing. Otherwise, his complete lack of compassion for Israelis, even when invited to show it, carries the whiff of prejudice. In the same interview, when challenged on his silence over the October 7 attack, Lineker said “I just feel for the Palestinians”; and you can read that word, “just”, in two different ways.

John McDonnell MP, Jeremy Corbyn’s right hand man when the Labour Party was dragged so deep into the shameful abyss of antisemitism that it broke anti-discrimination laws in its treatment of Jewish members, even had the chutzpah to laud the signatories of the Deputies’ letter as joining “that courageous band of Jewish people who have stood up for peace & an end to the killing.” Would any of these people truly have our backs if, in the metaphor of Nathan Englander’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, we Jews needed someone to hide us? We already have our answer. No wonder, when enablers and deniers of antisemitism are so quick to welcome and exploit any Jewish dissent from the Israeli government’s position, that Jews who love Israel but fear where its government is heading choose to share their thoughts only amongst trusted friends.

Yet given the growing and profound division between the Israeli government and the Israeli people over the war, a choice to stand with one is also a choice to diverge from the other. Supporting Israel can mean different things, when the Israeli government and the majority of the Israeli population are at odds over something as fundamental as war and the protection of its people. October 7 led to the phenomenon of the “October 8 Jews”: people who reconnected deeply with their Jewish identity and with Israel, not just due to of the horror of October 7, but because of the realisation that a lot of supposedly progressive allies actually supported it. Zionism, though, has never mandated a specific set of policies and views. For some, supporting Israel will always mean standing with its government, and that’s their choice: I’m not here to judge. But if the Israeli government makes this increasingly difficult for a growing number of Jews, that does not mean that their support for Israel as a whole has to wane.

For these people, perhaps the answer instead is to view supporting Israel as standing with the Israeli nation and its people, whether they are for the Israeli government or not. To support the hostages who remain in Gaza and their families, the soldiers already lost and those who are likely to die if the war is expanded as promised. And more deeply and just as urgent, to strengthen the moral and ethical values that Israel and Zionism are supposed to represent as an expression of Jewish nationhood.

Not a Jew but someone...who cares deeply about Israel and wants it to win its wars, understands the threats it faces and empathises with its impossible dilemmas; but at the same time, distrusts Netanyahu, despises the far right Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, despairs over this seemingly endless war and worries about the direction this government is taking the Jewish State: there is no landing place for you in British politics and society. No safe space outside the Jewish community to express this combination of views. Exactly fits me

Another excellent and thoughtful piece by Dave Rich. Should be required reading in many places not least the House of Commons, Broadcasting House and throughout Academia.