What links the Canadian Parliament, a Harry Potter concert in Portsmouth and a military show in Norfolk?

Back in April, the Guardian reported that a Ukrainian orchestra visiting the UK had to postpone some of its concerts because visas for its musicians were either delayed or refused, adding huge costs to their tour. The Guardian presented it as a story of Home Office incompetence, but what caught my eye was an unremarked-upon detail: the name of the orchestra itself.

This was the Khmelnitsky Orchestra from the Ukrainian city of Khmelnitsky, itself named after the 17th century Ukrainian nationalist leader Bogdan Khmelnitsky. He is a national hero in Ukraine, but his name is soaked in the blood of thousands of murdered Jews, slaughtered by his followers in a Cossack uprising against Polish rule in 1648 and 1649. And I thought of the Khmelnitsky Orchestra, playing music from Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings in Salford, York, Portsmouth and other venues around the UK, when I read about Yaroslav Hunka, the 98-year-old Waffen-SS veteran given a standing ovation in the Canadian Parliament a few days ago.

Hunka was a guest in the public gallery when the Canadian Parliament recently hosted Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and the Speaker Anthony Rota hailed Hunka as "a Ukrainian hero, a Canadian hero, and we thank him for all his service", prompting the applause. The problem is that Hunka was not one of the millions of Ukrainians who fought in the Red Army to liberate their land from Nazi occupation; he was one of the smaller, but still significant, number of Ukrainians who volunteered to fight with Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union. Hunka served in the 14th Waffen-SS Grenadier Division, and while he personally has not been accused or convicted of any war crimes, the division he served in has been implicated in massacres of civilians. The Waffen-SS itself was so steeped in the atrocities of the Nazi regime that the entire entity was declared a criminal organisation by the war crimes tribunal at Nuremburg.

This has caused a major fuss in Canada, prompting an apology from Prime Minister Trudeau and demands for Rota to resign. Poland’s Education Minister has even suggested seeking Hunka’s extradition.

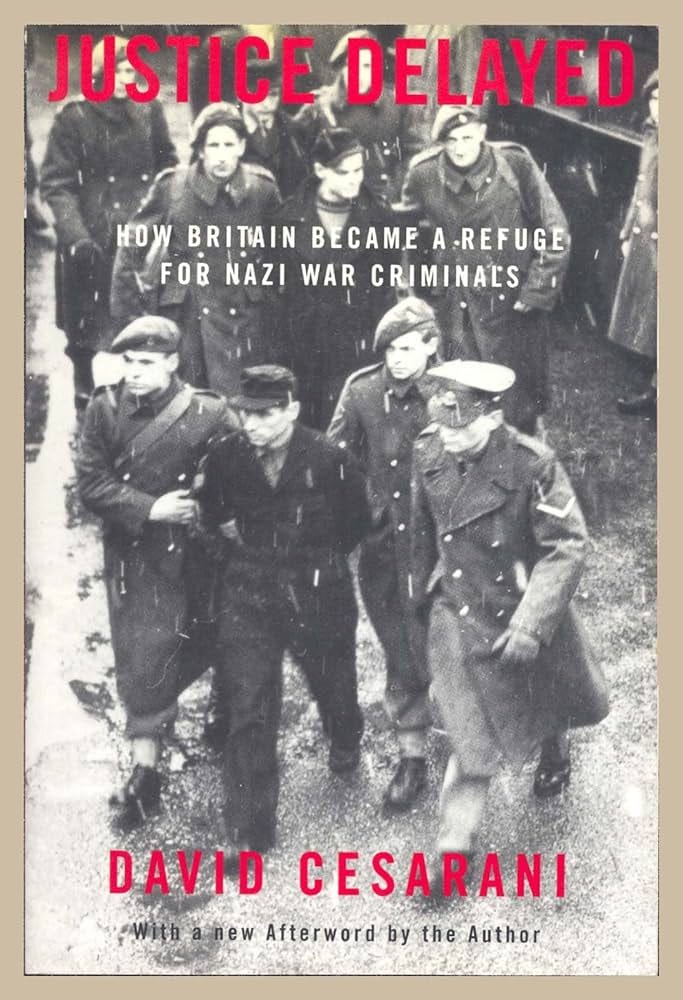

It isn’t a new revelation that thousands of Ukrainian and other volunteers who fought with the Nazis were allowed to settle in the West rather than being returned the Soviet Union, and Britain played a major role in this. David Cesarani devoted an entire chapter of his 1992 book Justice Delayed: How Britain became a refuge for Nazi war criminals to the story of how Hunka’s 14th Waffen-SS division, all 8,000 of them, ended up being granted residency in Britain in 1947. For many of them Britain was but a staging post to Canada or other countries of permanent residence: I don’t know for sure that Hunka was amongst those who passed through the UK, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

There’s a debate to be had about why this was allowed. Some see Cold War realpolitik playing a role in giving a haven to confirmed anti-communists, while the alternative - returning them to almost certain arrest and imprisonment in Stalin’s gulags, if not immediate execution - was not without its own moral difficulties. Cesarani details numerous examples of Whitehall officials overlooking concerns, deflecting Parliamentary questions, sanitising the unit’s record and showing little interest in screening its members in order to get the policy through. It is especially galling that while all this was going on the government went out of its way to prevent all but a handful of Jewish Holocaust survivors from gaining entry to Britain. But whichever side of that debate you come down on, one thing we shouldn’t be doing is celebrating Ukrainian Waffen-SS veterans as heroic defenders of their nation.

The uncomfortable truth is that there were a lot of non-Germans who volunteered for Hitler, and not all of them were living in parts of Eastern Europe where the need to choose between the vast armies of two totalitarian systems might at least provide some kind of ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’ context. In the same week that Yaroslav Hunka made his appearance in the Canadian Parliament, this historical amnesia regarding foreign volunteers for Nazi Germany also raised its head in Norfolk, of all places. A World War Two re-enactment event was going on in the village of Sheringham, and a row began when a group from the Eastern Front Living History Group turned up in SS uniforms. A spokesman for the group gave an unintentionally revealing explanation for their behaviour:

We represent the western European nations that fought against Stalin and communism during WWII. We were wearing Waffen SS infantry uniforms displaying national shields and insignia of the countries portrayed. Not one member of the group portrayed a German.

I don’t think this excuse works how they probably hoped it would, because the volunteers from western Europe who wore German uniforms to fight “against Stalin and communism during WWII” were Nazi sympathisers from within democratic nations. Of all the combatants in World War Two, they were perhaps the ones with the worst possible motivations for their choice. According to the Daily Mail, the Eastern Front Living History Group is in fact better known as the 5th SS Wiking Re-enactment Group. If this is true then it is even more damning because the SS Wiking division was directly involved in killings of Jewish civilians, especially towards the end of the war. You might wonder what is worse: a 98-year-old Ukrainian who may have committed war crimes, or a bunch of middle-aged British men who like to pretend that they did.

Contemporary politics sometimes brings these historical events back to life in unpredictable ways, and the presence of a Ukrainian Waffen-SS veteran at Canada’s Parliamentary celebration of President Zelenskyy has been seized upon by people who believe that modern Ukraine is a haven of neo-Nazis, or who have swallowed the Russian government line that their war is aimed at de-Nazifying their neighbour.

I’m always wary of people cherry-picking historical moments to support their ‘gotcha’ politics. We are constantly urged to learn from history, but it can mislead as easily as it enlightens (Whenever somebody tells you that the Daily Mail supported British fascism in the 1930s, try reminding them that the Daily Mirror did the same. It isn’t a reliable guide to their politics nearly a century later).

With that in mind, it’s worth stating that the current conflict in Ukraine is not a re-enactment of World War Two, despite the absurd claims of the Russian Foreign Ministry that they are fighting against “the ideology of the Holocaust” in the Ukrainian government (this is especially revolting given that Zelenskyy lost family members in the Holocaust). People like simple stories, with good guys and bad guys, where it is easy to pick a side. Right now, Western countries are supporting Ukraine against Russia, so it follows that people might assume a Ukrainian who fought for his country in the past can be hailed as a hero; except as the case of Yaroslav Hunka shows, history is a lot more complicated than that. Lost in all of this is the real, complex, contradictory story of the Jews of Ukraine, good and bad, the parts to celebrate and the parts to mourn, and the dead ends we run down if we try to use that history to work out who to support in today’s world. Which brings us back to Khmelnitsky.

The city of Khmelnitsky used to be called Proskurov, and in February 1919 Ukrainian nationalists slaughtered over 1,600 Jews there in one of the worst pogroms in the region. This was the period of the Russian civil war, when Ukrainian nationalists, White Russian forces, local bandits and Red Army troops all participated (to varying degrees) in violent, murderous, pogroms, and Ukraine became “the epicentre of antisemitism”. According to historian Gotz Aly:

Throughout Ukraine, Jews were burned alive in their homes, stabbed on the street in broad daylight, beaten and kicked to death, or gunned down… All the participants in the fighting treated them as fair game. The results were the worst pogroms in modern European history, carried out by tens of thousands of nationalist and socialist “freedom fighters.” We will never know how many Jews were murdered and how many of them, in particular women and children, starved or froze to death because their homes were burned down, all their belongings, provisions, and tools were stolen, their husbands and fathers were slaughtered.

Conservative estimates suggest at least 50,000 Jews were murdered in around 1,500 pogroms from 1918 to 1921, but the true figure is likely to be double that total. The army of the short-lived Ukrainian People’s Republic, led by Symon Petliura - himself still a hero for some in Ukraine - was the worst offender: they and their allies are estimated to have been responsible for 40% of the pogroms in Ukraine during those years and over 50% of fatalities. Petliura’s nationalist forces and his Cossack troops were consciously following a long pogromic tradition in Ukraine that began with Bogdan Khmelnitsky in the 17th century, which is why it is so jarring that an orchestra bearing his name (or the name of the city named after him) can blithely tour British concert halls today. In a strange way, this bothers me much more than Hunka getting a standing ovation from the Canadian Parliament, because at least that has resulted in a humiliating apology and a educational moment.

This is not just history: it’s personal. Like many British Jews I can trace part of my family to Ukraine, and when I read about the pogroms, massacres, deportations and exterminations that took place there over the past centuries, it’s my relatives and ancestors that I think about. My family kept in contact with their cousins in Lvov (as it was then known), visiting them and exchanging letters in the 1920s, until all communication ceased in 1942. I don’t know the details of their fate because, as Gotz Aly wrote about the post-WWI pogroms, too often “No one was left behind to report what had happened to them.” But I can hazard a guess. Ukrainian nationalists carried out a series of massacres in July 1941 shortly after the city was occupied by Nazi Germany, before most of the Jewish population was herded into a ghetto and eventually deported to the gas chambers of Belzec, or worked to death at Janowska labour camp.

I’ll admit it is discombobulating, to say the least, to now see a modern version of Ukrainian nationalism that appears for all the world to wrap its Jews in a warm embrace. It’s not just how absurd the Russian talk of de-Nazification seems; it is how unthinkable it would have been for Ukraine’s political leaders to have been Jewish in the time of Petliura or Khmelnitsky. It can simultaneously be true that, right now, Ukraine is fighting against Russian aggression, in line with Western values and interests, and is led by a popular and much-admired Jewish President; and that Ukrainian nationalism has, in the past, been responsible for some of pre-Holocaust Europe’s worst antisemitic bloodshed. But before anyone thinks differently, to make this point is not to sanitise the Russian historical record when it comes to antisemitism either. Life and history are not that straightforward.

When my ancestors left Ukraine and Poland around 120 years ago it was Russian rule they were fleeing. Jews were restricted by law in where they could live, what they could learn, the jobs they could do, the land they could own. Russia was a country where pogroms flared and Jews died, most notoriously at Easter 1903 in Kishinev (now Chișinău, the capital of Moldova), where 49 Jews were murdered and nearly 500 injured in a two-day orgy of violence. More than two million Jews emigrated from Russia between 1881 and 1914, 150,000 of whom ended up in the UK. The bulk of today’s British Jewish community traces its origins to that wave of migration, and the collective memory of Jewish life in the Russian shtetl is bitter sweet, as anyone who has watched Fiddler On The Roof will know.

The Soviet Union, especially under Stalin and his successors, systematically persecuted its Jewish inhabitants for decades and was a prolific generator of antisemitic propaganda, the legacy of which can be seen in left wing anti-Zionism today. And the current Russian government is happy to dabble in its own antisemitism when it suits. Whether it is Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, when asked how Ukraine can be run by Nazis when its President is Jewish, replying “So what if Zelenskyy is Jewish… I believe that Hitler also had Jewish blood. It means absolutely nothing. The wise Jewish people said that the most ardent antisemites are usually Jews.” President Vladimir Putin claiming that Western powers put an “ethnic Jew” in charge of Ukraine to mask its true Nazi character. Or the Russian embassy in London tweeting an antisemitic cartoon of a Zelensky as a big-nosed Jew:

This all ought to warn us against assuming that the misplaced and ignorant applause for Yaroslav Hunka tells us much about the state of antisemitism or Nazism in either Ukraine or Russia, now or in the past. At most, just as with the Khmelnitsky Orchestra’s tour of Britain and weird Nazi cosplaying in Norfolk, it only reminds us how little we remember; but also how much things can, and do, change.

Hunka did live in Britain for several years.

He also wrote a story of his life (with peculiar gaps) in 2011. 32 of 40 kids in his class were Jewish in 1941, before Hitler invaded USSR (according to Hunka). They were murdered over the next 2 years (not mentioned, but small town had around 30 Jews survive out of 32,000). Hunka calls these two years “the happiest of his whole life”. Then he joined Waffen SS. He had a long one.

Very interesting. Clearly it's right that "It can simultaneously be true that, right now, Ukraine is fighting against Russian aggression, in line with Western values and interests, and is led by a popular and much-admired Jewish President; and that Ukrainian nationalism has, in the past, been responsible for some of pre-Holocaust Europe’s worst antisemitic bloodshed."