I was honoured to give the keynote address at the Jewish community’s official Kristallnacht commemoration in Sydney last night. It turned out to be a much more timely and pertinent event than we realised, when I was originally invited to speak. This is the text of my speech.

Friends

Back in June, when I was invited to come to Australia to give this speech, I had in mind that it would be about Kristallnacht and the Shoah, and what we can take from that history to better understand where we are today. And I thought, to be honest, that it would be an enjoyable break from my work in the UK. But I have learnt over many years that when it comes to antisemitism, things don’t always work out how you expect, because, well, stuff happens. Antisemitism happens. And the past month has definitely been one of those moments in time.

I have worked in the field of researching and combating antisemitism for thirty years, and I have never known a period like this one. I don’t mean to be melodramatic. It’s not that people haven’t been killed in Israel before, including in shocking ways. That has been a feature of Jewish life between the river and the sea since before there was an Israel. Nor is it novel for Jews to be killed simply because they are Jews. In the past three decades we have seen Jews murdered by antisemitic terrorists in Argentina, France, Belgium, Denmark, the United States, Turkey, Tunisia, Morocco and other countries too. And of course, we are forced to endure outbursts of anti-Jewish hate every time Israel is at war.

But still, this feels different, because the slaughter and cruelty, in scale and character, of the Hamas pogrom on 7th October sent a shockwave through the Jewish world. This was not just another round of violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; it felt like an attack on all Jews, everywhere, a murderous assault on the Jewish people of a kind that we thought we had left in the past. Our history became our present reality.

We are here to commemorate Kristallnacht, to remember the horror of that night 85 years ago, and of course what then followed. Kristallnacht stands out for us as a marker on the path to the Nazi genocide, a stark, unavoidable warning sign of what was to come. And this is something we Jews do a lot: we look out for those warning signs. Many of us will have asked ourselves this question over the past month: what does this rise in antisemitism mean, not just for today but for our futures? How seriously do we have to take this? The novelist Philip Roth described history as “the relentless unforeseen… where everything unexpected in its own time is chronicled on the page as inevitable.” Often we only know what is inevitable with hindsight, but the history of antisemitism tells us that our wellbeing, perhaps even very our survival, might depend on our ability to foresee it in advance. We know now what Kristallnacht came to mean, of course. But at the time, who could tell?

Except back then, people did seem to know. It was Kristallnacht that led to the Kindertransport, the scheme that saw 10,000 Jewish children from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia travel unaccompanied to the United Kingdom, sent by their parents to live with strangers in a safer land. How did those thousands of Jewish parents know that this was the moment to take the ultimate risk and send their children to a foreign country, putting them in the care of strangers, in many cases with a full, if unspoken, understanding that they may never see their children again? I still wonder, not just as a Jew or as a student of antisemitism but as a parent, how they knew that was the moment to make the ultimate sacrifice, something you would only do when you have no other choice.

For our generation of Jews, who have grown up in relative safety and comfort in democratic, lawful, free societies, protected by our governments and with the ultimate security blanket of the State of Israel standing in the background, the past month has reminded us that we have largely not had to face this unfamiliar question, this unnerving feeling of insecurity.

And yet, when it comes to antisemitism nothing is ever really new. If you read contemporary accounts of the pogroms many of our great grandparents fled when they left Russia a little over a century ago, they are remarkably similar to what Hamas did, even down the smallest detail. According to one account of the pogroms that swept across Ukraine in the years immediately following the First World War, “Jews were burned alive in their homes, stabbed on the street in broad daylight, beaten and kicked to death, or gunned down. Entire families were murdered.” Anyone who knows the details of what happened in the kibbutzim of southern Israel on 7th October will find this chillingly familiar.

Then there are the heart-wrenching stories of Israeli parents hiding their children from gunmen coming to kill them. Keeping them silent for hours while they hid in their homes from people hunting them down. It has stirred deep, dark memories that Jewish people carry with us wherever we are.

There are important, fundamental differences that we must acknowledge. Hamas are not the Nazis. The State of Israel exists. It is not our governments and police carrying out the antisemitism; they are the ones trying to protect us from it. But seeing those images, reading those stories, has been – to use a modern term – triggering. The days of defenceless Jews being massacred in this way were supposed to be over. Yet here we are.

Antisemitism rhymes through the centuries, and in every generation there are people ready to write another verse.

And how have people responded to this?

In the Jewish community, as we know: shock, grief, fear, anger. I spend my days in the UK explaining to journalists, police officers, politicians and others how this has affected the Jewish community – how we all have friends and family in Israel, how there is generational trauma unearthed by this new pogrom – but I know that I don’t need to explain this to you.

I also think it has made Jewish communities feel more connected, both to Israel and to each other. I’ve been struck by how similar the issues you face here in Australia are to the challenges we have in the UK. The same types of hate crime, the same extremism, the same language and ideas driving it all. And it has made us all realise how much Israel’s existence underpins our innate sense of our own security and wellbeing as diaspora Jews, in a way that perhaps we did not fully acknowledge or articulate previously.

But what about everyone else?

Most people, in Britain and I’d like to believe here too, were horrified by what Hamas did and condemned it outright. Although actually, that’s not quite true. In Britain most people don’t care either way about Jews or Israel, don’t pay attention to the news, and don’t give any of this much thought at all. I don’t say this to be rude, and in a way I’m very comfortable with it. We are a tiny community, Israel is a tiny country, and we shouldn’t matter to others as much as we sometimes seem to. How things look from inside our bubble is not always how they actually are. But most people, I’m sure, are decent. They are appalled by terrorism, by antisemitism, by all the extremism that comes with it.

Still: whenever Israel is at war, we see huge demonstrations in towns and cities across the UK and other Western countries. No other foreign conflict generates a response of this scale or emotional intensity. It’s disturbingly unique. In London, on the first Saturday after the Hamas terror attack, 50,000 people marched. On the next Saturday, 100,000 people. And the same the Saturday after that. This is not normal.

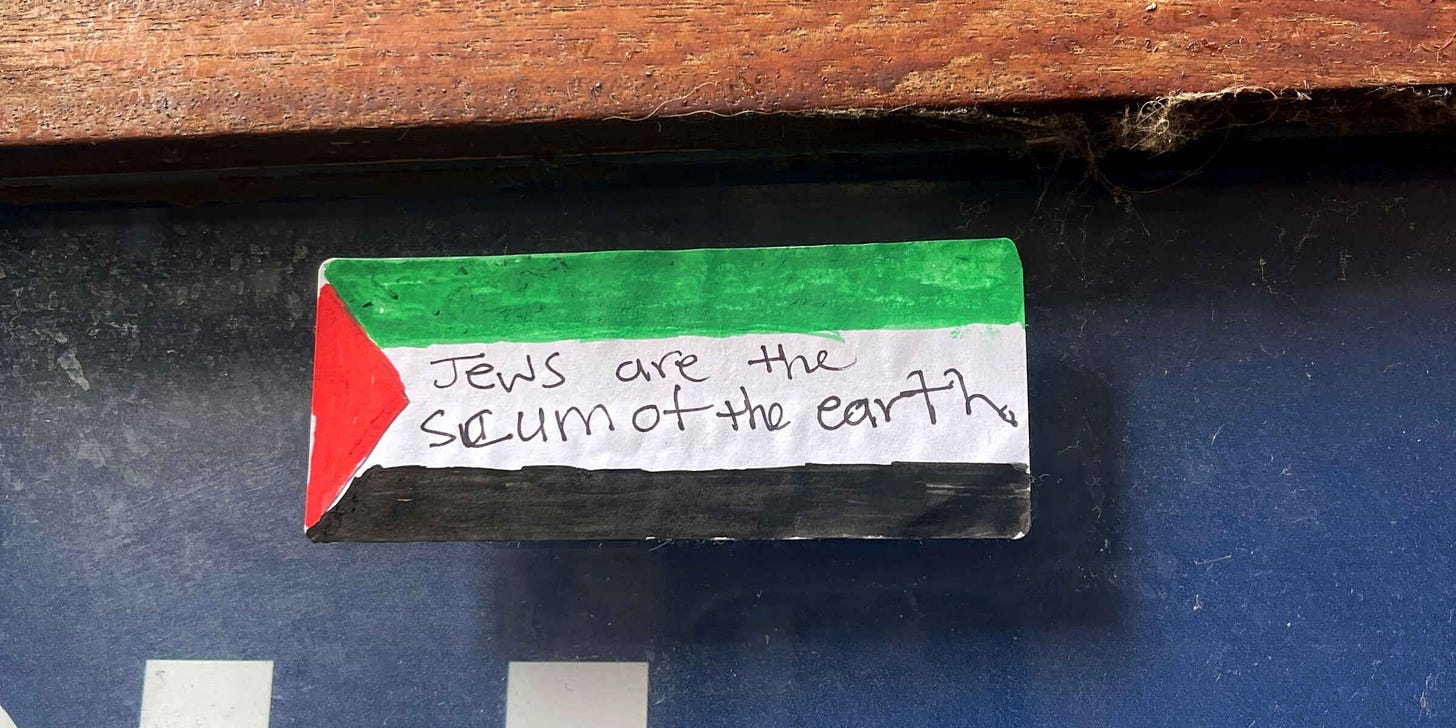

And this time it came with a twist. Because this time the conflict we are now witnessing began with a Hamas terror attack and the mass slaughter and kidnapping of Jews and others – we should not forget the many Israeli Arabs who were killed on 7 October, as were foreign workers of different nationalities – and the first anti-Israel demonstrations were organised within hours of that slaughter occurring, while Hamas terrorists were still in Israeli homes and Israel’s response in Gaza had barely begun. And those demonstrators did not go out to protest about anything Israel was doing. They went out to celebrate. We all saw the footage of the protest at the Opera House here in Sydney. There’s always a debate about what some anti-Israel slogans mean, and I’ll come back to that, but there’s no ambiguity about shouting “Gas the Jews”.

In Manchester, the city where I was born, the day after the attack people marched through the city centre carrying banners that read “Glory to the Freedom Fighters” and “Manchester Supports the Palestinian Resistance”. Before 7 October people could argue about the meaning of these words. That they represent legitimate military resistance, or that one person’s terrorist is another’s freedom fighter, and so on. But not now. Now we know exactly what Hamas’s version of “resistance” involves, and the unavoidable conclusion is that some people like it.

The same goes for the chant “From the River to the Sea, Palestine will be free”. Again, I’ve heard all the arguments in defence of this slogan. That it is simply a call for every Palestinian living in Gaza, the West Bank and Israel to have full civil rights. That it doesn’t mandate any particular political arrangement. But I don’t buy it, because I’m a big believer that in politics it’s the people actually putting things into action, turning ideas into reality, who carry the most weight. And when it comes to this slogan, it is Hamas who are trying to implement it, not the people chanting it in our Students’ Unions or on the demonstrations in our cities. And we know what Hamas mean by that slogan, because they have shown us: the ethnic cleansing of Jews in pursuit of a world in which Israel does not exist. That’s what it means in practice, so that’s what it means in theory.

I don’t think it’s fair to call every anti-Israel protestor antisemitic, or assume they all support Hamas. I’m sure that isn’t the intention of each and every one of them. But this is the political project on the ground that these protestors are lining up behind, whether they know it or not, whether they like it or not. And some do know it. The anti-Israel movement may not be intrinsically antisemitic, but it definitely attracts and excites antisemites. And in the hours and days following 7th October, we saw this more clearly than ever.

It sometimes feels like these spasms of antisemitism that crash onto Jewish communities at times like this come from nowhere, like a storm suddenly bursting out from a clear blue sky. But of course they don’t appear from nowhere. These waves of antisemitism, whether it is the hatreds that led to Kristallnacht or the antisemitism we are seeing today, are not superficial phenomena that come and go like the wind. They are the product of a deep-seated and long-held set of ideas about Jews that have been built into our world over many centuries. European civilisation has a global impact, and negative perceptions and depictions of Jews are woven into Europe’s highest culture and punctuate some of the most significant moments in our history. Day to day, they form a set of assumptions that some people just think they ‘know’ about Jews. In fact they don’t even “think” it, not in a conscious way.

The idea that propels most antisemitism, that gives it its thrust, its appeal and its deadly impact, is a simple one. It is the belief that Jews are always up to something. That they cannot be trusted, because they always have an ulterior motive or a hidden agenda, deploying their mysterious power and enormous wealth to achieve some particular Jewish goal. That they are innately harmful and threaten whatever society believes to be good, moral and wholesome. Or to flip it around, if something terrible, dangerous or frightening is happening in the world, whether it is war, terrorism, economic crash or global pandemic, some people cannot resist the temptation to find a Jew (or a bunch of Jews) to blame for it. Sometimes this is said about all Jews. Sometimes it is said about individual Jews, like the Rothschilds or George Soros. Sometimes these antisemitic assumptions are projected onto the State of Israel. It is a fantasy about the fearsome danger of Jewish wealth and power, combined with an assumption that Jewish malevolence threatens humanity.

And one reason why this keeps happening is simply that it always has done. This sounds banal, but it’s more important than you might think. People who fall for antisemitic myths and conspiracies, who follow these built-in assumptions about Jews, are like hikers following a trail across an unfamiliar landscape, who instinctively follow a path trodden into the earth by countless people before them in times long forgotten. It seems like the right thing to do – the right thing to think or say about the Jews – because these ideas have been around for so long, and are so familiar, that often we don’t even notice them. And this really does go back to the formative years of our culture, whether it is the Jews being blamed for the death of Jesus, or the medieval allegations of blood libels and well poisoning, or the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and the conspiracy theories of 19th and 20th century antisemitism.

It is even found within our most celebrated and cherished literature. Think of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, where you will find Shylock the moneylender, probably the best-known Jew in all of English literature. Or the character of Fagin in Oliver Twist. And you’ll also find it played for laughs in South Park and Family Guy. The Jew as a cunning, dishonest, greedy person, spiteful and cruel, who values only money and cares little for the higher Christian values of love and mercy. It’s a more common feature than we’d probably like to admit.

This idea about Jews translates from the most refined culture to the most base, ignorant comments in our everyday lives, and it’s woven into our language in ways we don’t even realise. A few years ago I was working with a well-known anti-racism body in England who were writing a guide to antisemitism for their stakeholders. They asked me to contribute a section about the Jewish community, so I drafted a few paragraphs about Jews in Britain – the usual stuff about where Jews life, the variety of religious practice, the things that Orthodox Jews will and won’t do on the Sabbath, that kind of thing. And I got an unexpected reply, a friendly query raised with some nervousness and sensitivity: is it really OK, they asked me, to use the word “Jew” rather than “Jewish people”, because isn’t “Jew” an insult?

I must stress, these were good people who were asking this question – people who would never themselves use the word “Jew” as an insult, but had obviously heard it used that way often enough to think that the word “Jew” – the word we Jews use to describe ourselves – is an offensive term. They were asking about it in good faith, and I didn’t mind: if anything I found it enlightening. This is not like most racist insults which are spat at the minority that is the intended target of the abuse. No: this insult is not flung at Jews, but deployed between people who aren’t Jewish and who insult each other by calling each other “Jew”, as if that is the worst thing anybody can be. You only have to look up the word “Jew” in the Oxford English Dictionary to know that these negative connotations have been part of our language for centuries.

I’ll give you one example of how the imprint of this history is seared into our world, and it’s an example that astonishes me every time I read it. In the late 1340s the Black Death ravaged Europe, killing between a third and a half of the population, and in many places Jews were blamed for spreading the plague by poisoning wells. In several towns in central Europe, Jews were arrested, expelled or burnt to death, with whole communities devastated. Alleged Jewish poisoners were tortured into ‘confessing’ that their crimes were supposedly part of a wider Jewish plot. The image of Jews as poisoners, either literally or metaphorically as a threat to the health of the nation, became fixed. Now here’s the amazing detail: 600 years later, antisemitic violence and support for the Nazi party in Germany in the 1920s and 1930s was higher in towns and cities that had also seen anti-Jewish violence and repression during the Black Death.

We know this because a pair of German economists decided to look into the data, and what they found was a remarkable persistence of attitudes across six centuries. Even when they accounted for the size, location, demography, economy and politics of different towns, they found that places that had witnessed violent attacks on Jews during the plague in 1349 also saw more antisemitic violence in the 1920s, more voters for the Nazi Party before 1930, people wrote more letters to the Nazi newspaper Der Sturmer, organized more deportations of Jews, and engaged in more attacks on synagogues.

Like I said, it’s an astonishing finding. Medieval antisemitism is liked a fossilised footprint in the bedrock of our civilisation, where water pools in the same way every time it rains. When we ask where all this antisemitism comes from, whether it is the antisemitism that led to Kristallnacht or the hatreds we see today, the answer starts with this history.

Of course, language changes. It modernises and adapts. The emblematic idea of the current wave of antisemitism is not the Nazi slogan “The Jews are misfortune”, or the earlier allegation that Jews are “Christ-killers”. It is that Jews are settlers and colonisers, racists and white supremacists. Much of the hatred we see now is driven by this idea that Israel, the nation state of the Jewish people, is not an authentic expression of Jewish identity but a product and a tool of Western imperialism, a settler colony with no greater legitimacy than French Algeria or British Rhodesia, and, like them, is destined to be washed away by history. The implication is that Jewish collective identity is not like other identities: either it is a hollow fraud because Jews are not worthy of calling themselves a people, and therefore are not deserving of the rights that come with that status; or it bears a uniquely malevolent stain that must be supressed for the good of humanity.

We’ve all seen the videos of people ripping down or defacing posters of the hostages held in Gaza. It’s sickening, and it’s difficult to fathom the heartlessness involved. There are a range of reasons why people do this, but one example that caught my eye in London involved a young man writing the word “Coloniser” over a set of posters. All of those Jewish hostages, male and female, young and old, even a two year old Israeli girl on one of the posters he defaced, all condemned as “colonisers”. It’s the new label through which Jews are dehumanised and turned into abstract representations of the latest thing that our society has designated as demonic.

This idea that Israel is a Western settler colony was part of Arab and Soviet propaganda for decades, and it fits neatly into the modern, identity-driven framing of all conflicts as manifestations of white supremacy and systemic racism. But it is academia that has done the most work to give it credibility and depth. Thousands of academics and students from 120 different British universities and colleges signed an open letter last month calling Israel “an ongoing settler colonial project” and demanding “recognition of the right to resist Zionist settler colonialism”. There was no qualification regarding attacks on civilians, because colonisers have no rights. This week over 250 academics at Australian universities put their names to a similar statement that argued “Since 1948, Palestinians have been subject to Israel’s ongoing project of settler-colonialism, ethnic cleansing, military occupation, and racial apartheid.” This statement made no mention of Hamas, or the 7th October pogrom, or of antisemitism or of hostages. And there are many other statements like this.

When we look around at the antisemitism that surrounds us today, at the huge number of people who care only about Palestine and no other international cause, who are happy to go along with a chant that calls for Israel’s destruction and think they are supporting human rights, who desperately contort the definition of “progressive” to justify cheering the genocidal violence of Hamas, who do not seem to care that antisemites are drawn to their movement: academia has a lot to answer for. No other sector of our society has put more heft, spent more time and energy, staked more of its reputation on embedding this belief about Israel and Israelis in the consciousness of the left. And the consequence of all this effort is the dehumanisation of Israeli Jews to such an extent that even beheading babies can be redefined as decolonisation.

Like I say, this has not come from nowhere. We’ve seen antisemitism gravitate from the fringes of our societies into mainstream politics in the United Kingdom and the United States, on different sides of the political divide. We see it in the role of social media platforms in connecting antisemites to each other, amplifying their views to millions. We see it in the popularity of conspiracy theories, especially amongst younger people. Perhaps this was all inevitable, given the political and social upheavals around the world in recent years. And this war has drawn together all these strands, like a magnifying glass catching the sun’s rays and focusing them into a beam strong enough to start a fire.

It does feel like we are entering a new phase. Perhaps this is just a reversion to the mean, after decades of relative tranquillity for Jewish communities. Perhaps this is the moment that post-Holocaust sensibilities finally evaporate for good. But that doesn’t mean it’s a time for despair; nor do we have the time to despair, either. We have built strong, resilient, successful communities that are worth protecting. We live in countries where antisemitism is seen as an ill that undermines core values, rather than a moral good that enhances them.

I know we are remembering Jeremy Jones this evening. I first met Jeremy over 25 years ago and had the pleasure of his friendship and wisdom ever since. I miss him, especially at a time like this. And I think his most admirable, and most powerful, quality was his optimism and his belief that we have many friends, and even more potential friends if we can reach them.

One of the lessons that Kristallnacht teaches us, and it is a lesson we see repeated throughout history, is that the moment of total danger for a Jewish community is when its government turns from protector to persecutor. If that happens, then – as we saw in Nazi Germany, and in different ways in the Soviet Union, in post-war Iraq and in modern-day Venezuela – Jewish communities can collapse very quickly. But as long as communities retain the support and protection of their government, police, all the authorities of state and our friends in wider society, they – we – can survive any crisis. And with the help of our friends, we will get through this one.

Thank you.

I just wanted to say, Jews matter to me and always have, many of my greatest heroes dead and alive have been Jewish. Jews mattered to my father too. He was a D Day Veteran, he was there at the liberation of the camps in Germany.